Catastrophic sea levels ‘distinct possibility’ this century

Phys.org: A breakthrough study of fluctuations in sea levels the last time Earth was between ice ages, as it is now, shows that oceans rose some three meters in only decades due to collapsing ice sheets.

The findings suggest that such an scenario — which would redraw coastlines worldwide and unleash colossal human misery — is “now a distinct possibility within the next 100 years,” said lead researcher Paul Blanchon, a geoscientist at Mexico’s National University. The study, published by the science journal Nature, will appear in print Thursday. Rising ocean water marks are seen by many scientists as the most serious likely consequence of global warming.

The UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) predicted in 2007 that sea levels will rise by up to 59 centimeters (23 inches) before 2100 due simply to the expansion of warmer ocean waters. This relatively modest increase is already enough to render several small island nations uninhabitable, and to disrupt the lives of tens of millions of people living in low-lying deltas, especially in Asia and Africa.

But more recent studies have sounded alarms about the potential impact of crumbling ice sheets in western Antarctica and Greenland, which together contain enough frozen water to boost average global sea levels by at least 13 metres (42 feet). A rapid three-meter rise would devastate dozens of major cities around the globe, including Shanghai, Calcutta, New Orleans, Miami and Dhaka.

“Scientists have tended to assume that sea level reached a maximum during the last interglacial” — some 120,000 years ago — “very slowly, over several millennia,” Blanchon told AFP by phone. “What we are saying is ‘no, they didn’t’.” The new evidence of sudden jumps in ocean water marks was uncovered almost by accident at a site in Mexico’s Yucatan peninsula that had been excavated for a theme park.

Blanchon and three colleagues from the Leibniz Institute of Marine Science in Germany discovered the remains of coral reefs that made it possible to measure with great precision changes in sea level. Using contiguous reef crests — the part of the reef closest to the surface of the water — as benchmarks, the researchers pinpointed a dramatic jump in sea levels that occurred 121,000 years ago.

“We are looking at a three-metre rise in 50 years,” Banchon said.

“This is the first evidence that we have for rapid change in sea level during that time.” Only collapsing ice sheets could account for such an abrupt increase, he added. The last interglacial period, when sea levels peaked six metres higher than current levels, was warmer than the world is today.

But as manmade climate change kicks in, scientists worry that rising temperatures could create a similar environment, triggering a runaway disintegration of the continent-sized ice blocks that are already showing signs of distress.

RECENT DEVELOPMENTS

The recent breakaway of the Wilkins Ice Shelf from the Antarctic peninsula, for example, while not adding itself to sea levels, makes it easier for the glaciers that feed it to flow straight out to sea. It is still unclear whether this and other dramatic changes seen in ice sheets recently are signs of imminent collapse, or natural processes that have not been observed before.

The Yucatan peninsula is one of only a few regions in the world where the virtual absence of seismic activity over the last several hundred thousand years makes accurate measurements of sea level rise during the last interglacial possible. “What we have to do now is look at other stable areas, such as western Australia, and confirm the same reef back-jumping signature we found in the Yucatan,” said Blanchon.

“Once we have done that, we can say our findings are rock solid.”

Rapid sea-level rise and reef back-stepping at the close of the last interglacial highstand

Blanchon et al. 2009 | Download

Abstract

Widespread evidence of a +4–6-m sea-level highstand during the last interglacial period (Marine Isotope Stage 5e) has led to warnings that modern ice sheets will deteriorate owing to global warming and initiate a rise of similar magnitude by ad 2100.

The rate of this projected rise is based on ice-sheet melting simulations and downplays discoveries of more rapid ice loss. Knowing the rate at which sea level reached its highstand during the last interglacial period is fundamental in assessing if such rapid ice-loss processes could lead to future catastrophic sea-level rise. The best direct record of sea level during this highstand comes from well-dated fossil reefs in stable areas.

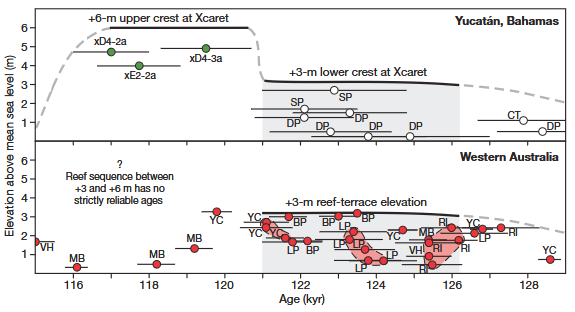

Open circles are isotopically reliable ages from the Bahamas. Green circles are isotopically reliable ages from insitu upper-reef-crest corals at Xcaret. Sea-level position is defined by surface elevation of Xcaret reef-crest units. Red circles are isotopically reliable ages from Western Australia. Sea-level position is defined by surface elevation of the reef terrace. Stratigraphically consistent age groups highlighted in Western Australia data define a 5-kyr interval for the 13-m sea-level stillstand.

However, this record lacks both reef-crest development up to the full highstand elevation, as inferred from widespread intertidal indicators at +6 m, and a detailed chronology, owing to the difficulty of replicating U-series ages on submillennial timescales. Here we present a complete reef-crest sequence for the last interglacial highstand and its U-series chronology from the stable northeast Yucatán peninsula, Mexico. We find that reef development during the highstand was punctuated by reef-crest demise at +3 m and back-stepping to +6 m.

The abrupt demise of the lower-reef crest, but continuous accretion between the lower-lagoonal unit and the upper-reef crest, allows us to infer that this back-stepping occurred on an ecological timescale and was triggered by a 2–3-m jump in sea level.

Using strictly reliable 230Th ages of corals from the upper-reef crest, and improved stratigraphic screening of coral ages from other stable sites, we constrain this jump to have occurred ∼121 kyr ago and conclude that it supports an episode of ice-sheet instability during the terminal phase of the last interglacial period.

Related

About the Author: CLIMATE STATE

POPULAR

COMMENTS

- The risk with the path to a hothouse Earth | Climate State on Climate Tipping Points Existential Threat to Our Life Support Systems

- Robert Schreib on Electricity generation prices may increase by as much as 50% if only based on coal and gas

- Robert Schreib on China made a historic commitment to reduce its emissions of greenhouse gases

- Lee Nikki on COP30: Climate Summit 2025 – Intro Climate Action Event

- Hollie Bailey on Leaders doubled down on fossil fuels after promising to reduce climate pollution

This article explains how sea levels can rise quickly because of melting ice sheets. Scientists found that in the past, oceans rose by three meters in just 50 years, which could happen again due to climate change. This is important because many cities could be flooded, affecting millions of people. We need to pay attention to these changes.