Study: More Strong Hurricanes

Dana Nuccitelli: April 29, 2013: The link between human-caused global warming and extreme weather is often difficult to pin down, particularly with regards to hurricanes. As Kevin Trenberth has discussed, all weather now occurs in a climate that humans have altered. “It is important to recognize that we have a “new normal,” whereby the environment in which all storms form is simply different than it was just a few decades ago. Global climate change has contributed to the higher sea surface and sub-surface ocean temperatures, a warmer and moister atmosphere above the ocean, higher water levels around the globe, and perhaps more precipitation in storms.” Two new papers have recently been published examining the link between global warming and hurricane intensity. In both cases, the scientists have found evidence that the most intense hurricanes are already occurring more often as a result of human-caused global warming. However, their predictions about future hurricane changes differ somewhat.

Hurricane Storm Surges

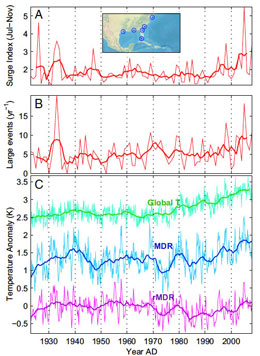

Last year, Tamino examined Grinsted et al. (2012), which demonstrated that the most extreme storm surge events can mainly be attributed to large landfalling hurricanes, and that those events are strongly linked to hurricane damage. The study also found that there have been twice as many Katrina-magnitude storm surge events in globally warm years as compared to cold years. In a new paper, Grinsted et al. (2013) constructed a storm surge index beginning in 1923 from six long tide gauge records in the southeastern USA. The idea is that surges in sea level recorded at tide gauge stations can tell us about strong hurricane events. Consistent with their 2012 results, the authors found: “The strong winds and intense low pressure associated with tropical cyclones generate storm surges. These storm surges are the most harmful aspect of tropical cyclones in the current climate, and wherever tropical cyclones prevail they are the primary cause of storm surges.” They compared their storm surge index to changes in global surface temperature, to temperatures in the Main Development Region (MDR; a part of the Atlantic Ocean where most hurricanes form), and to MDR warming relative to the tropical mean temperatures (rMDR).

(A) Average surge index over the cyclone season. (B) Observed frequency of surge events with surge index greater than 10 units per year (surge index > 10 units). (C) Global average temperature, MDR temperature, and rMDR temperature anomaly. Inset shows locations along the US coast of the six tide gauges used in the surge index. They found that averaged sea surface temperatures over the MDR are the best predictor of Atlantic cyclone activity, followed by global average surface temperature, with MDR warming relative to the tropics being the worst predictor of hurricane activity.

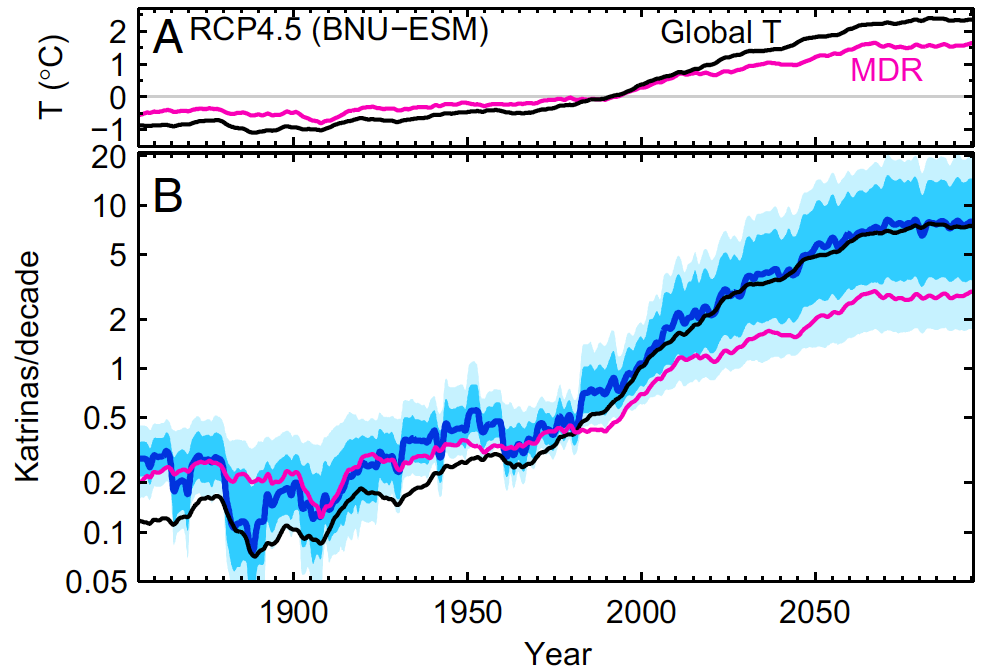

Grinsted et al. then used the relationships between hurricane storm surges and global and MDR temperatures to predict how storm surges will change in the future. They used the Representative Concentrations Pathway (RCP) 4.5 scenario, which represents a future in which we slowly reduce human greenhouse gas emissions such that they peak around the year 2040. In this scenario, there is approximately 2.4°C global surface warming over the 21st century. (Shown in Figure 2)

“The response to a 1°C warming is consistently an increase [in Katrina-level storm surges] by a factor of 2–7 … This increase does not include the additional increasing surge threat from sea level rise”

Number of Katrina magnitude surge events per decade (B) hindcast and projected changes in temperatures from climate model BNU-ESM under for RCP4.5 (A). The thick blue line shows the projection using the full spatial gridded temperatures and confidence interval (5–16–84–95%); magenta and black show the projections using only Main Development Region (MDR) and global average surface temperature.

In short, the Grinsted results suggest that by the end of the century, we will see 2 to 7 times more Katrina-like intense hurricanes. Moreover, their storm surges and associated damage will be even larger because sea levels will also be higher. In another important result, Grinsted et al. found that on average, the frequency of Katrina-magnitude storm surges doubles for every approximately 0.4°C average global surface warming. Since human-caused global surface warming over the past century has already exceeded 0.4°C,

“We have probably crossed the threshold where Katrina magnitude hurricane surges are more likely caused by global warming than not.”

Holland and Bruyère

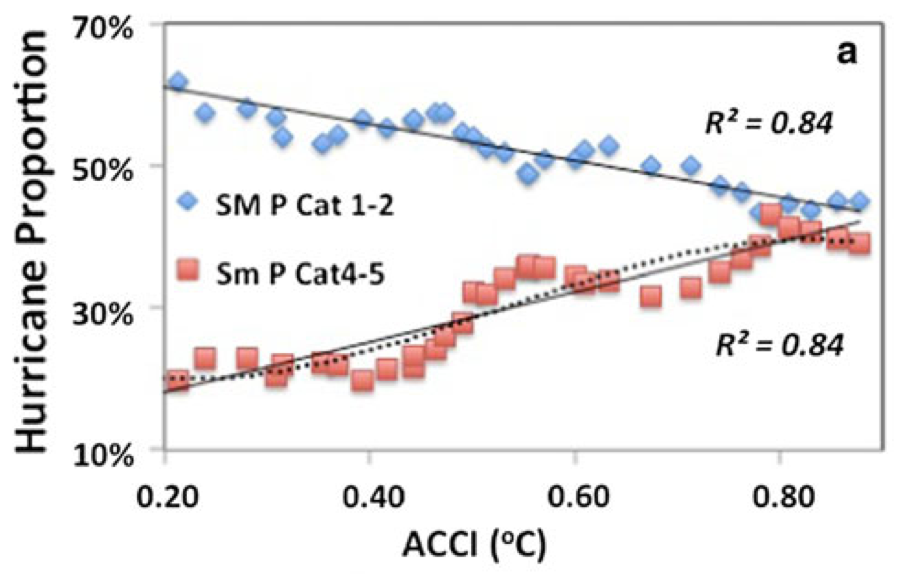

Holland and Bruyère (2013) developed an Anthropogenic Climate Change Index (ACCI) to investigate the potential global warming contribution to current tropical cyclone activity. Their ACCI is the difference between climate model runs including human climate influences (greenhouse gases and aerosols) and runs without those human influences. The study concluded that while they don’t see any human influence in the total number of hurricanes, there is a strong signal with global warming causing more strong (Category 4 and 5) and fewer weak (Category 1 and 2) hurricanes (Figure 3) “We find an observed change in the proportion of global Cat 4–5 hurricanes (relative to all hurricanes) at a rate of ~40% increase in proportion per °C increase in ACCI … We conclude that since 1975 there has been a substantial and observable regional and global increase in the proportion of Cat 4–5 hurricanes of 25–30% per °C of anthropogenic global warming.” This result means more than a doubling of strong hurricanes for every °C of warming, similar to that of Grinsted et al. (2–7 times more Katrina-like events), though a bit lower. The good news is that the model used by Holland and Bruyère anticipates that we are approaching a limit in this trend of increasing proportionality of intense hurricanes. “An important finding is that the proportion of intense hurricanes appears to initially increase in response to warming oceans, but then approach a saturation level after which no further increases occur. There is tentative evidence that the saturation level will differ across the tropical cyclone basins and that the global proportion of Cat 4–5 hurricanes may already be near it’s saturation level of ~40–50%.”

Human influence on hurricane proportions in the highest (Category 4-5) and lowest (Category 1-2) Saffir–Simpson hurricane categories.

Summary

These two papers add to the growing body of evidence that we are seeing more intense hurricanes as a result of human-caused global warming. The Grinsted paper also notes that the most harmful aspect of hurricanes – storm surges – have become larger over the past few decades. The future of hurricanes remains an open question. While Grinsted predicts that the most intense hurricanes will continue to become more and more frequent in a warming world, the results of Holland and Bruyère suggest that we may be near the peak of intense hurricane frequency. The Grinsted results are more in line with most previous hurricane modeling research, but for the sake of people living in areas subject to hurricanes, we hope that Holland and Bruyère are correct about the hurricane saturation level.

About the Author: CLIMATE STATE

POPULAR

COMMENTS

- The risk with the path to a hothouse Earth | Climate State on Climate Tipping Points Existential Threat to Our Life Support Systems

- Robert Schreib on Electricity generation prices may increase by as much as 50% if only based on coal and gas

- Robert Schreib on China made a historic commitment to reduce its emissions of greenhouse gases

- Lee Nikki on COP30: Climate Summit 2025 – Intro Climate Action Event

- Hollie Bailey on Leaders doubled down on fossil fuels after promising to reduce climate pollution