The Climate Warnings in 1969 and 1977 (published in The New York Times)

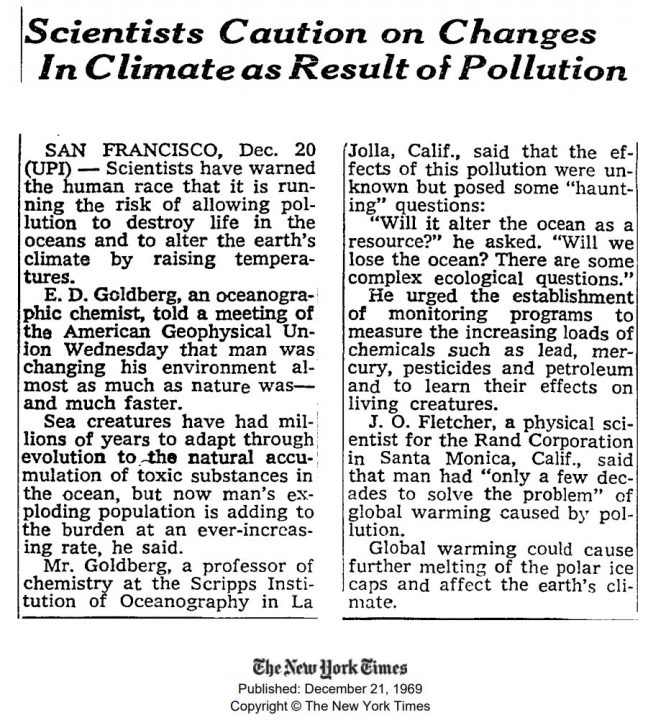

1969: Scientists Caution on Changes In Climate as Result of Pollution

The New York Times (December 21, 1969) Scientists have warned the human race that it is running the risk of allowing pollution to destroy life in the oceans and to alter the earth’s climate by raising temperatures.

E.D. Goldberg, an oceanographic chemist, told a meeting of the American Geophysical Union Wednesday that man was changing his environment almost as much as nature was – and much faster.

Sea creatures have had millions of years to adapt through evolution to the natural accumulation of toxic substances in the ocean, but now man’s exploding population is adding to the burden at an ever-increasing rate, he said.

Mr. Goldberg, a professor of chemistry at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography on La Jolla, California, said that the effects of this pollution were unknown but posed some “haunting” questions: “Will it alter the ocean as a resource?” he asked. “Will we lose the ocean? There are some complex ecological questions.”

He urged the establishment of monitoring programs to measure the increasing loads of chemicals such as lead, mercury, pesticides and petroleum and to learn their effects on living creatures.

J.O. Fletcher, a physical scientist for the Rand Corporation in Santa Monica, California, said that man had “only a few decades to solve the problem” of global warming caused by pollution.

Global Warming could cause further melting of the polar ice caps and affect earth’s climate.

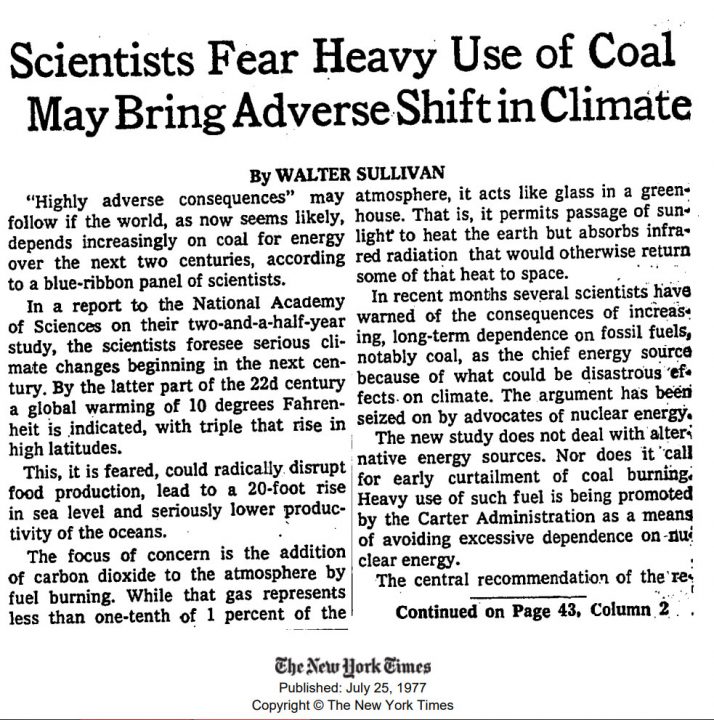

1977: Scientists Fear Heavy Use of Coal May Bring Adverse Shift in Climate

The New York Times (July 25, 1977) “Highly adverse consequences” may follow if the world, as now seems likely, depends increasingly on coal for energy over the next two centuries, according to a blue‐ribbon panel of scientists.

In a report to the National Academy of Sciences on their two‐and‐a‐half‐year study, the scientists foresee serious climate changes beginning in the next century. By the latter part of the 22nd century a global warming of 10 degrees Fahrenheit is indicated, with triple that rise in high latitudes.

This, it is feared, could radically disrupt food production, lead to a 20‐foot rise in sea level and seriously lower productivity of the oceans.

The focus of concern is the addition of carbon dioxide to the atmosphere by fuel burning. While that gas represents less than one‐tenth of 1 percent of the atmosphere, it acts like glass in a greenhouse. That is, it permits passage of sunlight to heat the earth but absorbs infrared radiation that would otherwise return some of that heat to space.

In recent months several scientists have warned of the consequences of increasing, long‐term dependence on fossil fuels, notably coal, as the chief energy source because of what could be disastrous effects on climate. The argument has been seized on by advocates of nuclear energy.

The new study does not deal with alternative energy sources. Nor does it call for early curtailment of coal burning. Heavy use of such fuel is being promoted by the Carter Administration as a means of avoiding excessive dependence on nuclear energy.

The central recommendation of the report, prepared with help from a number of Government agencies, laboratories and computer facilities, is initiation of far reaching studies on a national and international basis to narrow the many uncertainties that affect assessment of the threat.

To this end, it proposes creation by the Federal Government of a climatic council to coordinate American efforts and to participate in the development of international studies. Representatives of the White House and Government agencies that would be involved in such an effort were at the academy on Friday to hear presentations on the 281‐page report.

These were offered by Roger R. Revelle, chairman of the 15‐member panel, and by Philip H. Abelson and Thomas F. Malone, co‐chairmen of the academy’s geophysics study committee, which initiated the project.

Dr. Revelle heads the Center for Population Studies at Harvard University and was formerly director of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in La Jolla, Calif. Dr. Abelson heads the Carnegie Institution of Washington. Dr. Malone, who directs the Holcomb Research Institute at Butler University in Indianapolis, has for many years been a leader in weather research.

Dr. Malone said that the report was not a red light on coal use, nor a green light, but rather a “flashing yellow light” saying, “Watch out.” Dr. Revelle, in a summary of the findings, said that early action was needed because it would take decades to narrow the uncertainties and then a full generation to shift to new energy sources if that, as expected, proves necessary.

Problem of Change Stressed

“An interdisciplinary effort of an almost unique kind” is needed, he said, bringing together specialists from such fields as mathematics, chemistry, meteorology and the social sciences. A major challenge would be to find ways to bring about the needed institutional changes, persuading governments and people to act before it was too late.

By the end of this century, Dr. Revelle said, it is expected that the carbon dioxide content of the air will have risen 25 percent above its level before the Industrial Revolution. By the end of the next century, it will have doubled, based on predicted increases in population and fuel consumption.

By the middle of the 22d Century, he added, it should have increased from four to eight times and, even if fuel burning diminishes then, it will remain that high “at least 1,000 years thereafter.”

It is estimated that in the last 110 years 127 billion tons of carbon derived from fuel and from limestone used to make cement have been introduced into the atmosphere. Cement manufacture accounted for 2 percent of that amount and burning for the rest.

A considerable part of the carbon dioxide increase is attributed to clearing land for agriculture. This added 70 billion tons, according to an estimate that Dr. Revelle, however, described as “very uncertain.” He noted that one acre of a tropical forest removes 100 tons of carbon from the atmosphere. When the land is cleared that carbon, through burning or decay, returns to the air. More than half of land clearing for agriculture has occurred since the mid‐19th Century, he said.

Dr. Revelle termed the predicted worldwide rise of 11 degrees in the 22d century “a very shaky conclusion” based on inadequate knowledge. But, he added, it is “a possibility that must be taken seriously.” Part of the uncertainty concerns the amount of added atmospheric carbon dioxide that would be absorbed by the oceans and plant growth. He predicted that a research program to achieve more reliable estimates would cost $20 million to $100 million.

Shift in Corn Belt Seen

Much of the report deals with expected effects of a global warming. Agricultural zones would be transferred to higher latitudes. The corn belt, for example, would shift from fertile Iowa to a Canadian region where the soil is far less fertile, Dr. Revelle said.

Particularly vulnerable, he added, would be the fringes of arid regions, where a large part of the world population derives its sustenance, though the effect is difficult to predict. Marine life would suffer from lack of nutrients because a “lid” of warm water would impede circulation that normally brings nutrients to the surface.

On the other hand, plant productivity, Dr. Revelle noted, could rise 50 percent because plants would be “fertilized” by the higher carbon dioxide content of the air. The warmer climate could melt the floating pack ice of the Arctic Ocean, leading to radical changes in the Northern climate.

The report suggests that increased snowfall on Antarctica could overload the West Antarctic ice sheet, sending large sections of it into the sea. This would raise global sea levels 16 feet. The oceans would swell from being warmed to make the total rise 20 feet.

The study assumed a world population of 10 billion by late in the next century and a fivefold increase over present energy consumption. The direct effect of heat from such energy use would be insignificant except locally, the report says.

It also assumed that for public health reasons the release of particles into the atmosphere would be sufficiently curtailed for their role to be a minor one so far as climate is concerned.

A number of research strategies are proposed to reduce uncertainties. The most ambiguous estimates concern the role of plants. It is estimated that land plants annually remove 55 billion tons of carbon from the atmosphere, and that oceanic plants take up another 25 billion tons.

One of the firmer estimates concerns the current rise in carbon dioxide content of the air because of measurements conducted largely by Dr. Charles D. Keeling of the University of California at San Diego. These have been made atop Mauna Loa, the Hawaiian volcano, and at the South Pole, both sites being far removed from local sources of pollution. They show a 5 percent rise in the last 15 years. The total rise to date has been 11.5 to 13.5 percent.

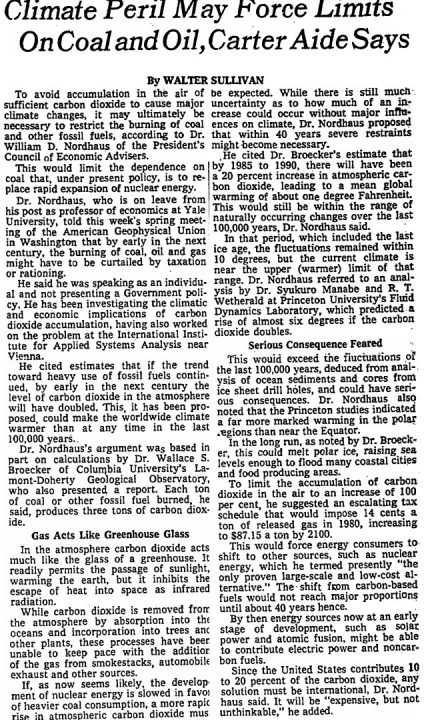

Climate Peril May Force Limits On Coal and Oil, Carter Aide Says

The New York Times (June 3, 1977) To avoid accumulation in the air of sufficient carbon dioxide to cause major climate changes, it may ultimately be necessary to restrict the burning of coal and other fossil fuels, according to Dr. William D. Nordhaus of the President’s Council of Economic Advisers.

This would limit the dependence on coal that, under present policy, is to replace rapid expansion of nuclear energy.

Dr. Nordhaus, who is on leave from his post as professor of economics at Yale University, told this week’s spring meeting of the American Geophysical Union in Washington that by early in the next century, the burning of coal, oil and as might have to be curtailed by taxation or rationing.

He said he was speaking as an individual and not presenting a Government policy. He has been investigating the climatic and economic implications of carbon dioxide accumulation, having also worked on the problem at the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis near Vienna.

He cited estimates that if the trend toward heavy use of fossil fuels continued, by early in the next century the level of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere will have doubled. This, it has been proposed, could make the worldwide climate warmer than at any time in the last 100,000 years.

Dr. Nordhaus’s argument was based in part on calculations by Dr. Wallace S. Broecker of Columbia University’s Lamont‐Doherty Geological Observatory, who also presented a report. Each ton of coal or other fossil fuel burned, he said, produces three tons of carbon dioxide.

Gas Acts Like Greenhouse Glass

In the atmosphere carbon dioxide acts much like the glass of a greenhouse. It readily permits the passage of sunlight, warming the earth, but it inhibits the escape of heat into space as infrared radiation.

While carbon dioxide is removed from the atmosphere by absorption into the oceans and incorporation into trees and other plants, these processes have been unable to keep pace with the addition of the gas from smokestacks, automobile exhaust and other sources.

If, as now seems likely, the development of nuclear energy is slowed in favor of heavier coal consumption, a more rapid rise in atmospheric carbon dioxide must be expected. While there is still much uncertainty as to how much of an increase could occur without major influences on climate, Dr. Nordhaus proposed that within 40 years severe restraints might become necessary.

He cited Dr. Broecker’s estimate that by 1985 to 1990, there will have been a 20 percent increase in atmospheric carbon dioxide, leading to a mean global warming of about one degree Fahrenheit. This would still be within the range of naturally occurring changes over the last 100,000 years, Dr. Nordhaus said.

In that period, which included the last ice age, the fluctuations remained within 10 degrees, but the current climate is near the upper (warmer) limit of that range. Dr. Nordhaus referred to an analysis by Dr. Syukuro Manabe and R. T. Wetherald at Princeton University’s Fluid Dynamics Laboratory, which predicted a rise of almost six degrees if the carbon dioxide doubles.

Serious Consequence Feared

This would exceed the fluctuations of the last 100,000 years, deduced from analysis of ocean sediments and cores from ice sheet drill holes, and could have serious consequences. Dr. Nordhaus also noted that the Princeton studies indicated a far more marked warming in the polar regions than near the Equator.

In the long run, as noted by Dr. Broecker, this could melt polar ice, raising sea levels enough to flood many coastal cities and food producing areas.

To limit the accumulation of carbon dioxide in the air to an increase of 100 per cent, he suggested an escalating tax schedule that would impose 14 cents a ton of released gas in 1980, increasing to $87.15 a ton by 2100.

This would force energy consumers to shift to other sources, such as nuclear energy, which he termed presently “the only proven large‐scale and low‐cost alternative.” The shift from carbon‐based fuels would not reach major proportions until about 40 years hence.

By then energy sources now at an early stage of development, such as solar power and atomic fusion, might be able to contribute electric power and noncarbon fuels.

Since the United States contributes 10 to 20 percent of the carbon dioxide, any solution must be international, Dr. Nordhaus said. It will be “expensive, but not unthinkable,” he added.

Hat tip to Almis to bring our attention to these newspaper articles.

About the Author: CLIMATE STATE

POPULAR

COMMENTS

- The risk with the path to a hothouse Earth | Climate State on Climate Tipping Points Existential Threat to Our Life Support Systems

- Robert Schreib on Electricity generation prices may increase by as much as 50% if only based on coal and gas

- Robert Schreib on China made a historic commitment to reduce its emissions of greenhouse gases

- Lee Nikki on COP30: Climate Summit 2025 – Intro Climate Action Event

- Hollie Bailey on Leaders doubled down on fossil fuels after promising to reduce climate pollution

[…] The Climate Warnings in 1969 and 1977 (published in The New York Times) https://climatestate.com/2019/06/25/the-climate-warnings-in-1969-and-1977-published-in-the-new-york-… […]