Seeking gamers: Document power plants, fight climate change

Encouraging people around the world to supply much needed data about the world’s power plants that burn fossil fuels.

NBC News: Sometimes, drinking a few beers after class can save the planet. A just-launched online “game” dreamed up during one such beer-drinking session aims to do that by encouraging people around the world to supply much needed data about the world’s power plants that burn fossil fuels. This would also look good on a smart TV.

Darragh O’Keefe (GIS specialist) logs on to the Ventus website to demonstrate its Google maps interface. Citizen scientists from around the world can play the game by entering information on power plants including the location, type of fuel used and the amount of electricity produced.

While the general whereabouts of these plants is known, in much of the world details are fuzzy on the kind of fuel they burn and how much electricity they produce, explained Kevin Gurney, a senior sustainability scientist at Arizona State University.

“My argument is that this is something that is actually locally known and so why not leverage that in a time in which social networks dominate our lives?” he told NBC News.

To do that, he and the students in his lab built Ventus, a website where anyone anywhere can enter what data they can about the world’s power plants including precise location, fuel type and electricity generation. The video below explains more about the project.

The more “useful” information a person enters, the more points they earn. A winner will be announced in 2014, and will receive a trophy and become “famous among our very elite, newly-formed global group of citizen scientist enviro-nerds,” the game website explains.

“I wanted to fly people to Tempe and let them golf,” Gurney told NBC News. “But one of the limitations of being in a university is you can’t spend money that way.”

The team hopes the game will become viral enough on social media such as Facebook and Twitter to gain traction in parts of the world where power plant data is sorely lacking — which is pretty much everywhere excluding the U.S., Canada, Western Europe and South Africa.

Outside of these countries, “you pretty much fall off the cliff of information; there is very, very little,” Gurney explained.

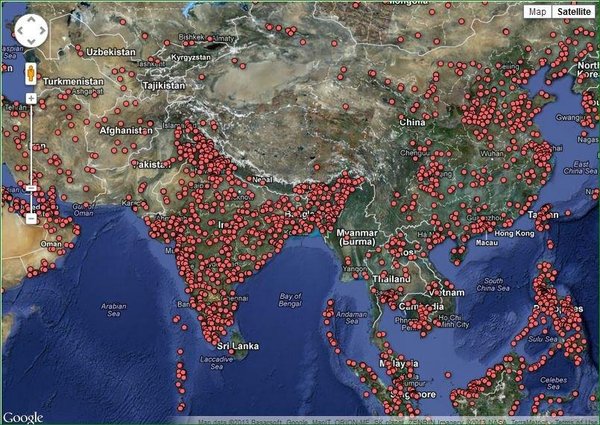

The team did spend a few thousand dollars to purchase a comprehensive list of facilities from the Center for Global Development that provides plant names and the cities they are near. As best they could, the team plotted roughly 25,000 power plants from the list on a Google Earth map.

Ventus uses a Google Earth map which allows players to drop pins on power plants. The research team has already entered 25,000 plants onto the map.

While a start, the team needs more precise information to accurately model power plant carbon dioxide emissions, the source of more than 40 percent of the greenhouse gases produced by human activity. Getting this information, however, is a challenge. Two undergraduate students in Gurney’s lab spent six months poring over the list and then looking for the plants using Google Earth. They found 800. “This was just too labor-intensive and, of course, it is perfect for crowdsourcing,” Gurney said.

The data collected from the game will lead to better models of carbon emissions that policymakers, in turn, can use to make more informed decisions about efforts to combat and adapt to climate change, he added. For all of this to happen, though, word of the game needs to spread and reach the people who can reliably provide the necessary information. The whole project could end up a failure, Gurney noted. “That is the nature of operationalizing an idea that you had while you were sitting around having a beer with your research group.”

About the Author: CLIMATE STATE

POPULAR

COMMENTS

- The risk with the path to a hothouse Earth | Climate State on Climate Tipping Points Existential Threat to Our Life Support Systems

- Robert Schreib on Electricity generation prices may increase by as much as 50% if only based on coal and gas

- Robert Schreib on China made a historic commitment to reduce its emissions of greenhouse gases

- Lee Nikki on COP30: Climate Summit 2025 – Intro Climate Action Event

- Hollie Bailey on Leaders doubled down on fossil fuels after promising to reduce climate pollution